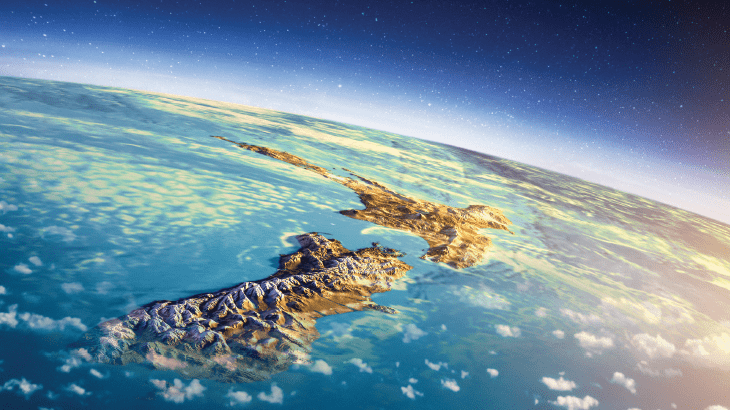

View Auckland -

The migration equation

In the decade to 2020, New Zealand experienced some of the developed world’s strongest population growth, yet, we built amongst the fewest new homes for our residents.

The result was one of the fastest escalations in real residential values, brought about by a potent combination of flexible migration policy, low interest rates, and a favourable economic climate which saw the property market boom.

Flash forward to the start of the global health crisis, which disrupted established migration patterns as border restrictions catalysed an enormous decline in net migration inflows.

So valuable was migration to our biggest economic contributors – housing and construction - that policymakers acted quickly to offset the most negative implications, dropping the Official Cash Rate (OCR) to record low levels and implementing a comprehensive fiscal programme tasked with encouraging investment and keeping the country’s economy afloat.

After several years of net migration losses, Aotearoa-New Zealand’s population is again on the rise, and pundits are speculating what it means for residential property values. Can we expect to see property values rise as the population increase places pressure on our housing supply?

From pause to progress

With New Zealand operators facing intense capacity constraints brought about by a tight labour market and skills shortages in critical areas, including healthcare, construction and education, the Government has made various changes to its migration settings, including greater occupational scope for the Straight-to-Residence Visa criteria.

This visa allows applicants from selected disciplines to live, work, and study in New Zealand, along with their partners and dependent children up to 24 years of age, providing one of the quickest pathways to New Zealand residency for many migrants.

The return to more flexible migration settings comes at the same time a recent report from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) ranked New Zealand as the best country in the world on matters including quality of life, family inclusivity, income, tax and the ability to attract highly skilled workers.

The result is a sharp rise in migration that’s forecast to see population growth rise from just 0.5 percent at the end of 2022 to more than two percent by the close of this year – the fastest New Zealand has seen in decades.

Whilst good news for businesses which depend on valuable skills and work experience to increase productivity, the rapid rise in migration and the resurrection of the tourism industry could see the economy cling on to growth for longer than expected, as unemployment remains near record lows and clingy Consumer Price Inflation (CPI) persists.

The Reserve Bank (RBNZ) downplayed the impact of this demand in its latest Monetary Policy Statement (MPS), where it increased the OCR by 25 basis points to a cyclical high of 5.5 percent. However, the migration question contrasts awkwardly against its efforts to bring inflation down from 6.8 percent to within the one-to-three percent target band, and continues to add a demand dynamic at an inconvenient time.

Marginal or meaningful?

What role the current surge in migration will have on economic and housing market activity remains to be seen. However, the stabilisation of residential values has continued in recent months, at the same time, average weekly rental values are tracking upward.

Data from Statistics New Zealand shows average weekly rents are up 3.8 percent year-on-year as landlords anticipate greater demand from an increase in new migrants seeking homes. At the same time, evidence suggests a looming downturn in residential construction, with new building consent figures down 25 percent from a year ago.

Record-high migration figures from April assume New Zealand’s population growth is running at an annualised rate of more than 140,000 – suggesting population growth of circa 2.5 percent per annum – some five times faster than the level assumed by government statisticians and infrastructure planners.

This incongruence will continue to pressure the housing supply, with commentators noting that if persistent, New Zealand could be facing another housing shortage of circa 30,000 dwellings by this time next year. A return to a supply-demand deficit will likely result in potential value uplift of residential assets.

With sales activity picking up, buyer classification data shows the influence of foreign capital, as migrants now make up around 13 percent of New Zealand’s recent house hunters.

This share has steadily increased over the last four years and almost doubled since 2021.

Despite this, migration is not the only influential factor weighing on residential demand, and rising mortgage lending rates and an uncertain global economy look set to keep pressure on affordability in the mid-term.

Persistently high domestic inflation on everything from food to vehicles and electricity continues to see Kiwis taper back spending on non-essential items, which means affordability remains a key constraint for many in the current economic environment.

In the coming months, population growth will provide a meaningful shot in the arm for residential sales activity. However, this is expected to be tempered by uncertainty surrounding October’s general election and the unveiling of housing policy, in addition to implications surrounding debt-to-income tools and the ongoing impact of higher mortgage lending rates.

In short, migration will help to put a floor underneath the residential housing market, with values set to move upward from here, though we’re unlikely to see a return to the previous cycle’s market high.